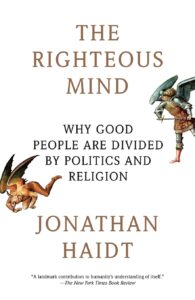

Jonathon Haidt

Nonfiction 2012 | 419 pages (includes 101 pages of notes, etc.)

![]()

An astounding read! This book answers the simple but essential question: Why don't we all get along? Published in 2012, it does not address the Trump era specifically, but the knowledge and insight hold today. The confounding mystery of how good people can be SO divided as we are today in our political world is finally explained. What Haidt has to say is very revealing. We are divided by our different moral compasses ... moral foundations, he calls them. And none are bad. No one is foolish or idiotic. And, in fact, the right, which has a broader moral compass than the left (conservatives subscribe to more morals) is much better at navigating these differences than the left, who are more tightly focused on just a few moral principles.

In The Righteous Mind, moral psychologist Jonathan Haidt explains why liberals, conservatives, and libertarians all have different understandings of right and wrong. (He also applies his works to the religious and non-religious.) We have different moral frameworks. He argues that moral judgments are emotional, not logical—they are based on stories that evolve in our lives, rather than reason. Consequently, liberals and conservatives lack a common language, and reason-based arguments about morality are ineffective, leading to political polarization.

The Righteous Mind builds this argument on three basic principles:

- Morality is more intuitive than rational.

- Morality is about more than fairness and harm.

- Morality “binds and blinds” us.

No surprise ... I read a few reviews, most of which are either five star or one star! You will love or hate this book. Whatever you think of his proposal, Haidt gives us a framework for looking at why we differ so much, and for, perhaps, being less judgmental about those who seem to reach some very different conclusions.

My only criticism of the book is that Haidt labels theories and ideas by the name of the professor or clinician who has researched and published. So, the theories bear names like “Kant, Shweder, and Durkheim.” For a lay person like myself, not familiar with these professorial researchers, I would have comprehended what he was saying if he labeled the theories descriptively and didn’t call them by the researcher’s name. I could not remember who said what about what.

For the first 100 pages or so, I was in the place of “Huh. I am smart, but I am not sure I understand what he is saying.” But I was definitely intrigued. And so I kept going, and he really did make sense of it all for me.

I think this book is REQUIRED reading, not just a recommendation. Many thanks to wonderful artist and watercolor teacher Suze Woolf (I have two of her paintings over my guest bed) for this inspired read. (https://www.suzewoolf-fineart.com/)

(p.s. I was delighted to learn how the terms "left" and "right" came about! See pg 277)

September 2021